23 March 1944

Paolo

Sun glinted on the Colosseum but Paolo barely noticed. The dustcart he pushed was heavy and the afternoon unseasonably warm. He was already sweating profusely.

He wanted to look behind, but his comrades were following and they would protect his back.

The Via dei Fori Imperiali led uphill and, as Paolo dragged the cart over the cobbles, he saw its contents slide precariously. He was a twenty-one-year-old medical student not a dustman and this task was far from easy.

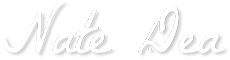

He passed the Foro Triano, relieved that he was making progress, and struggled through Piazza del Quirinale.

‘Hey, you!’

Two dustmen approached him.

‘What are you doing here? This isn’t your zone.’

‘Nothing,’ Paolo stammered. ‘I’m carrying a load of cement.’

One smiled: ‘Oh, I understand: you’re in the black market too! Go then.’

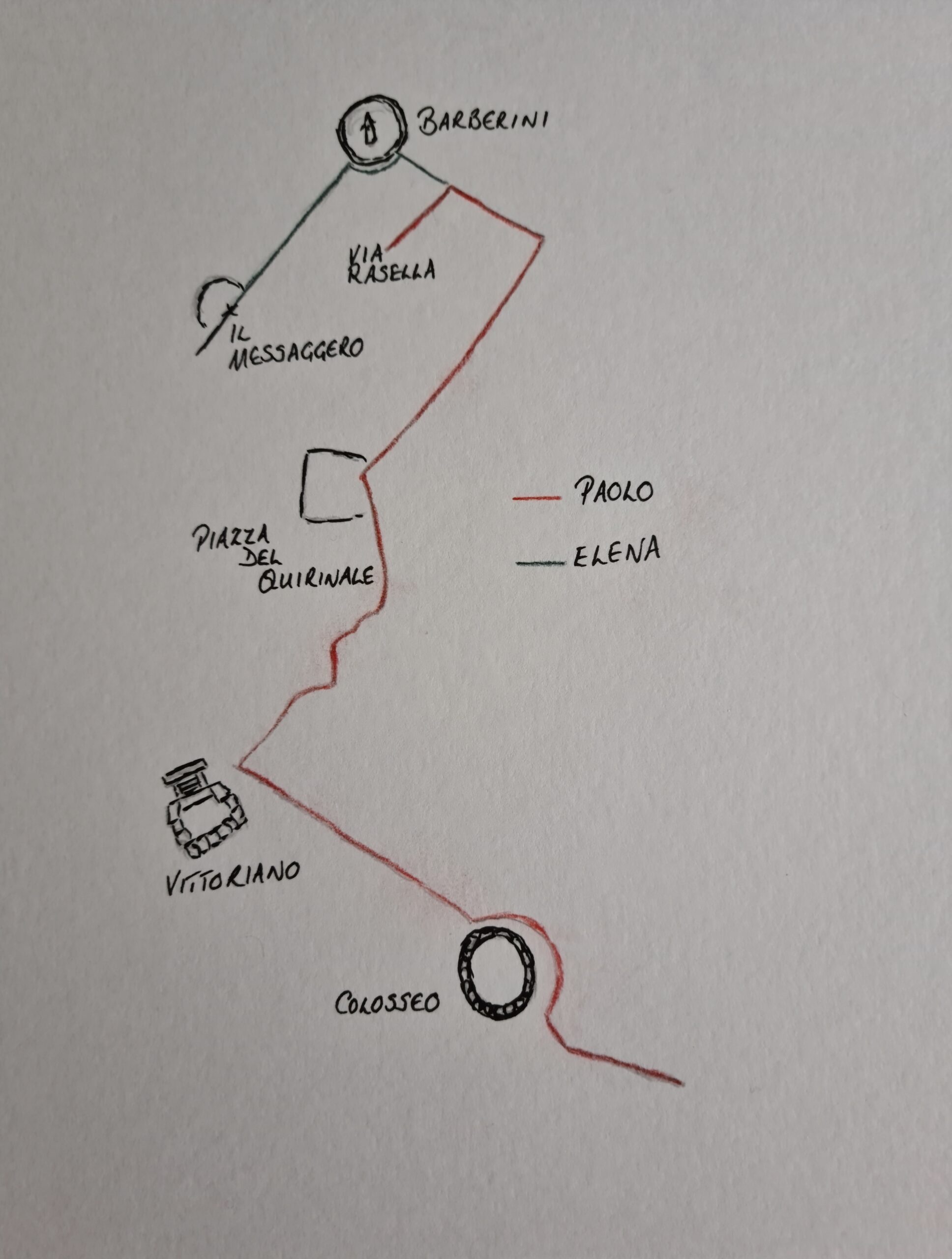

Paolo followed Via del Quirinale until he reached Via delle Quattro Fontane. Here, he turned left, where the road sloped downwards towards Barberini. Downhill should have easier but he had to cling onto the cart to stop it running away.

Paolo turned left into Via Rasella and halted the cart in front of Palazzo Tittoni at number 155.

Elena

Meanwhile, Elena stood in Largo del Tritone, outside of the offices of Il Messaggero, Rome’s principal newspaper. She was waiting for a signal and pretended to read the newspaper displayed in a case. The paper reported a recent eruption of Mount Vesuvius but Elena’s eyes darted to the reflection of Pasquale in the glass.

She strained her ears for any sound of marching soldiers. The SS Bozen Regiment marched past every day and Pasquale was supposed to signal as soon as he saw them. The soldiers were late: had they changed their plans?

Elena knew that she had been here too long and thought nervously of the gun she was hiding. Worse still, she had a man’s raincoat draped over her arm and it was a lovely day, with no likelihood of rain.

Two men stood nearby: policemen, she guessed. They joined her.

One asked: ‘Are you waiting for someone?’

‘My fiancé: he works in Palazzo Baberini,’ Elena replied.

‘Why are you carrying that raincoat?’

‘It’s my fiancé’s. I cleaned it for him and I’m giving it back,’ she said.

Elena saw Pasquale move towards her.

‘What time is it?’ she asked the men.

‘2.47,’ one replied.

‘I must go then.’

Elena hurried away past Pasquale, who tried to tell her something. She could not hear him and assumed that he had given her the signal. Now she walked uphill to Barberini, along Via delle Quattro Fontane and halted at the top of Via Rasella.

Elena saw Paolo and peered down the slope, expecting to see the first of the soldiers, but there was no sign of them. Once more, she had to wait.

Two more policemen joined her and she explained again that she was expecting her fiancé, who worked in Palazzo Barberini. The men said that they would wait with her and her heart sank. She, Paolo and the others were risking their lives and the police presence made their position even more perilous.

Help came from an unexpected source: Elena saw an elderly friend of her mother and, excusing herself to the policemen, rushed over to her. The lady must have been surprised at the warmth of the greeting but Elena chatted to her for as long as she could, hoping that the police would lose interest.

The plan

Via Rasella is a quiet road, sloping uphill to Via delle Quattro Fontane. Each day in March 1944, soldiers of the SS Bozen regiment marched through Rome on the way back to their barracks, and Via Rasella was one of the narrower and quieter roads on their route. Elena and Paolo were members of Gap, a prominent resistance group in Rome, and they had identified Via Rasella as a place for an ambush.

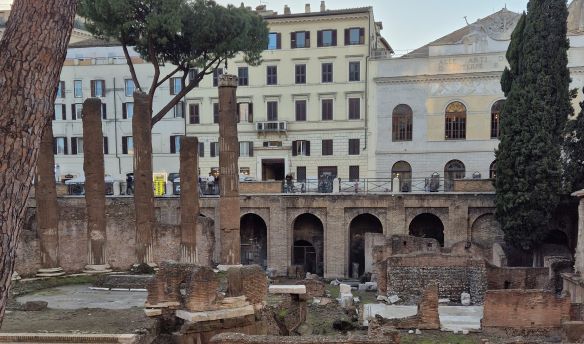

Paolo’s cart held a hidden bomb, and a group of partisans were in position close by, at the crossroads of Via del Boccaccio and Via dei Giardini. Once the partisans heard the explosion from Paolo’s cart, they would join the attack with bombs of their own. Two other Gap members, Spartaco and Cola, were positioned in Via Rasella.

The attack

On 23 March, the soldiers were extremely late. Usually, they arrived shortly after 2.00 but it was close to 4.00 when Cola, positioned at the start of Via Rasella, signalled to Paolo that the German soldiers were coming.

Paolo lit the fuse and rushed towards Elena but he saw an elderly Italian soldier emerge from a building. Paolo hissed: ‘It’ll be slaughter here soon: the Germans are coming.’ Fortunately, the man understood and hurried inside.

Paolo heard the Germans’ footsteps as he raced uphill. He reached Elena and donned the raincoat to cover his dustman’s jacket, slipping the gun into his pocket.

The roar of the explosion was enormous and extended down Via delle Quattro Fontane, where a tram skidded to a halt. As the partisans lobbed their own bombs, Paolo and Elena boarded the halted tram and escaped.

Soldiers fired shots, unsure who or where their attackers were, but thirty-two German soldiers already lay dead in Via Rasella. Another German soldier died in the hours after the attack and more died later of their injuries. Two Italian civilians were also killed, innocent victims of the chaos. None of the resistance members or partisans was captured or injured.

German officials, more soldiers and police arrived. The inhabitants of Via Rasella were lined up in the road and their apartments searched, but it soon became apparent that they had not been involved.

Today, the only signs of the attack are the marks left by gunshots on the walls of one of the buildings in Via Rasella, close to Via Boccaccio.

24 March 1944

The German leaders in Rome and Berlin were furious, even threatening to blow up the area.

General von Mackensen, the direct superior to the military head in Rome, gave the order. For each German killed, ten Italians would be executed, selected from prisoners already sentenced to death. The order was given to the commander of the SS Bozen soldiers who had been killed but, incredibly, he refused, arguing that it was a police matter. The responsibility passed to Colonel Kappler, head of the Gestapo in Rome.

There were insufficient prisoners already sentenced to death in Rome and Kappler and his men added other names to the list, including men still awaiting trial. Kappler also demanded prisoners from the Italian police chief, Caruso, and the fascist groups in Rome.

The prisoners were driven away from their prisons in unmarked trucks covered with tarpaulin. Many believed that they had been selected for forced labour and were told that their clothes and belongings would follow. Their destination was the Ardeatine Caves, a short distance from the centre of Rome.

The trucks travelled in and out of Rome until the evening, ferrying their human cargo. Within Rome, people saw the trucks and wondered. The trucks might have been taking supplies to the front but they were unmarked, which was both unusual and strange.

Three hundred and thirty-five men were driven to the Ardeatine Caves. One, an Austrian deserter, escaped but the others were shot by Kappler and his men. When they had finished, Kappler’s men blew up the entrance to the caves, hoping to conceal what they had done.

The aftermath

Inevitably, the truth came out, initially through a farmer who worked nearby and a local monk. Soon, people began to leave flowers at the site.

The Germans sent letters, in German, to the families of those who had been executed. The letters gave the date of death, 24 March 1944, but not the location or circumstances. The letters in many cases added:

“Personal effects may be requested from the offices of the German SS in 155 Via Tasso, where they are stored.”

Today, the Ardeatine Caves stand as a monument to those who were executed. Almost all of the men are listed, their ages ranging from fifteen to sixty-nine. They came from diverse walks of life, for example: lawyer, doctor, accountant, carpenter, driver, electrician, travelling salesman, operatic tenor, colonel, police officer.

Paolo and Elena were the resistance names of Rosario Bentivegna and Carla Capponi. They continued their resistance activities outside of Rome and married after the war. He became a doctor and she a member of parliament.

Colonel Herbert Kappler was sentenced to life imprisonment after the war. The court found that he had sent more men to their deaths than had been ordered in response to the thirty-three soldiers killed. In 1977, he escaped from a military hospital. The official (and barely credible) story was that his wife smuggled him out in a suitcase. He died the following year, a free man, in Germany.