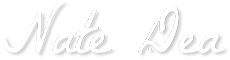

Teatro Marcello has two storeys of arches – empty apart from the ghosts – but, above, are glazed windows.

The upper floors are occupied.

The pathway past Teatro Marcello leads to the Portico d’Ottavia and the start of the historic Jewish ghetto.

The dome of the synagogue is in the centre of this photo and part of the residence – a palazzo – is on the left.

Travel down the Capitoline Hill (Via Teatro Marcello) and you will see the palazzo adjoining Teatro Marcello. Its main entrance is on the other side.

Near the foot of the hill is the church of St Nicola in Carcere. The photo shows the lower edge of the palazzo and, next to it, the front of the church.

For the palazzo’s main entrance, turn right after the church and right again.

Here, the Lungotevere, bordering the river, changes from the Lungotevere Pierleone to the Lungotevere di Cenci. Just ahead is the Ponte Fabricio and on the right, in the Piazza di Monte Savello, are excavations. They began in 1999 and, it is believed, reveal a second ghetto.

This photo shows part of the excavations, overlooked by the palazzo.

This second ghetto is sometimes referred to as the Ghettarello or Macelletto and inluded homes, a synagogue, grain stores, bakeries and stables.

Via Monte Savello is a small road, just after the excavations.

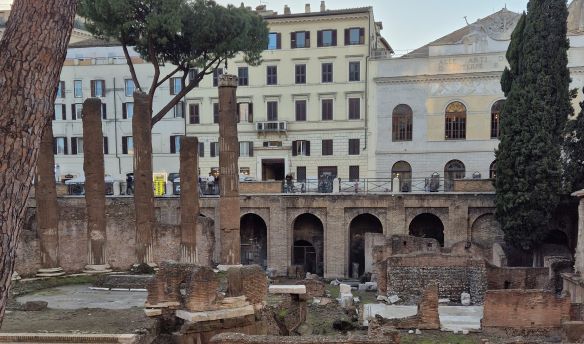

It reaches a dead end and, on the left, no 30, is the entrance to Palazzo Savelli Orsini, the residence that adjoins and rises above Teatro Marcello.

The first proprietors were the Savelli family. In the early sixteenth century, they transformed the original fortress into a renaissance residence. The work involved demolishing a significant part of Teatro Marcello; the garden is located where the seating section of the theatre used to be.

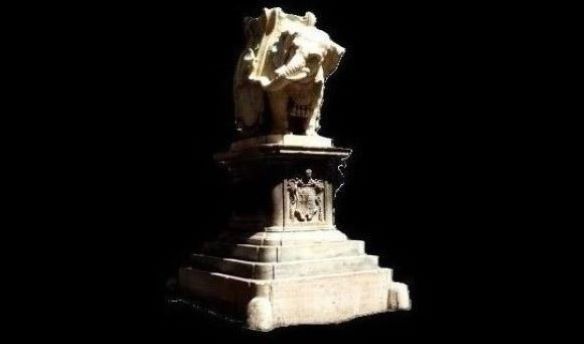

The Orsini family acquired the palazzo in 1729 and the entrance to the garden is guarded by two bears, their symbol.

Neither the palazzo nor gardens are open to the public but, during the German occupation, they were a refuge for fugitives, including at least one Allied serviceman.

The Princess

Vittoria Colonna was born in 1880 in London, where her father was stationed. She was part British, on her mother’s side, but her father was the Prince of Paliano, Marcantonio VI Colonna, and Vittoria was brought up as an Italian aristocrat in Rome.

In 1901 Vittoria married Leone Caetani; it was a dynastic marriage between two aristocratic families. They had a son, Onorato, born in 1902 and, around that time, Leone purchased the Palazzo Savelli Orsini.

On the death of his father in 1917, Leone inherited the titles Prince Teano and Duke of Sermoneta, whilst Vittoria became the Princess and Duchess.

Reportedly, the couple had little in common: he was academic, studious, and became a politician with liberal democratic leanings. Vittoria, meanwhile, was outgoing, sociable, a lover of art and sport. She was an able horsewoman and sufficiently adventurous to fly an air balloon. For a while, she was nicknamed: “The Ballooning Princess”!

With the Great War, Leone went to the front as an artillery officer.

In June 1916, Vittoria travelled to the small island of San Giovanni on Lake Maggiore. She had spent the summer there for several years, with her son and a few domestic servants. This summer, one of the guests at a nearby villa was the painter Umberto Boccioni. He was on leave from the front, painting the portrait of the pianist Ferruccio Busoni.

The villa’s aristocratic owners invited Vittoria to a party and Umberto made an instant impression. Vittoria wrote to her husband that the “jolly boy” was full of vivacity and intelligence. In fact, Vittoria and Umberto made a profound impression on each other.

Once Busoni’s portrait was finished, Umberto left for Milan but returned by train at the beginning of July, to be met by Vittoria. She was thirty-five and he was thirty-three. They spent only a week together, as he had to return to the front, but they agreed to write, and expected to be together again in the future.

Umberto’s letters made his feelings clear. He even told Vittoria that he was learning to ride horses, so that, after the war, they could go riding together. He posted his last letter to her on 16 August 1916, just before he went out to ride. Something – perhaps a vehicle – startled his horse and he was thrown, hitting his head. He died a few hours later.

On the morning of 19 August, Vittoria wrote her last letter to Umberto. She read about his death shortly afterwards in the newspaper. Vittoria kept his letters hidden in a trunk and they were found only in 2006.

Vittoria and Leone separated, probably in 1917. He left for Canada in 1927, with his mistress and their daughter, who was born in 1917. Leone remained in Canada until his death in 1935.

World War II

Vittoria was in Rome when the Germans occupied the city in September 1943. The palazzo became a refuge for fugitives, including at least one British serviceman (many had been in northern Italy at the time of the Armistice and were trying to join the Allied forces in the south).

The palazzo is overlooked only from a distance and Via di Monte Savello is quiet, looking out onto the ruins of the Capitoline hill.

The wall to the right in the photo belongs to the Church of San Nicola in Carcere.

By the beginning of 1944, the Germans had infiltrated much of the resistance and were closing in on the safe houses.

At the end of January, Vittoria’s butler arrived to announce:

“Not dinner, Madam, but the police.”

Vittoria was placed under house arrest.

Later, she evaded her German captors, on the pretext of changing her clothes, and fled to the neutral Spanish Embassy.

Postscript

Vittoria died in 1954, six years after the death of her only son, in 1948.

The palazzo became divided between various owners but in 2012 the Orsini family once more bought a significant part.

Vittoria’s letters from Umberto Boccioni were used as the basis for a book by Marella Caracciolo Chia: Una Parentesi Luminoso