Rome’s famous prison was originally built as a convent.

Its name, Regina Coeli, means “Queen of the Heavens”.

Living in Regina Coeli

In 1944, Marcella Monaco was twenty-six years old. She was a mother of two young children and married to Alfredo, a prison doctor at Regina Coeli. He was on call most nights and the family apartment was within the prison complex. Their door was a short distance from the main prison entrance at 28 Via della Lungara and their window overlooked the prison courtyard.

Most of the prison staff were unaware that Marcella and Alfredo were members of the socialist party and had joined a resistance group, the Matteotti group. They risked arrest because of this.

Marcella and Alfredo often hosted meetings of the Matteotti group at their apartment; it felt like a safe place because no-one would expect that in Regina Coeli! Sometimes, one or two of the group members spent the night at the apartment and Marcella would give them food. Alfredo had patients in the countryside who had little money but paid him with whatever they had, such as flour, eggs and meat, which supplemented the family’s rations.

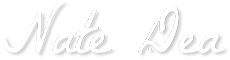

Regina Coeli in 1944

Regina Coeli had several different wings. Some were occupied by ordinary criminals but two were designated for political or resistance prisoners. One wing was under Italian control and the other run by the Germans.

Alfredo was able to travel through the Italian section and would pass and receive messages, sometimes with the aid of helpful warders. He had some access to the German controlled wing, but his movements there were restricted, and he was watched more closely. If prisoners fell ill, he could visit them in the infirmary at any time.

Marcella, like Alfredo, had considerable freedom within the Italian section, as she helped to look after the guards’ children and gave them clothes and toys. The guards’ wives confided in her, and Alfredo gave them medical treatment free of charge.

Regina Coeli was overcrowded, and conditions throughout were grim, but political prisoners preferred to be in the Italian wing. The prison governor, Donato Carretta, tried to help the inmates where he could but his powers were limited in the German wing. There were stories of prisoners being tortured there and, by early 1944, an increasing number of its inmates were deported for forced labour.

A planned escape

The Matteotti group discussed plans to liberate seven socialist party members from Regina Coeli. Two, Pertini and Saragat, were important members of the Matteotti group, but they were held in the German wing.

The group included two lawyers, who had contacts within the justice system and, somehow, they arranged for the transfer of Pertini and Saragat into the Italian wing. All seven were now in the Italian-controlled section.

A few members of the Matteotti group favoured an escape from the prison windows, using ropes. Marcella and Alfredo disagreed; they knew the prison well and told their colleagues that it would be impossible. The only way out for seven men at once would be to stage their release.

Preparing the papers

The group set to work preparing release papers. The group’s two lawyers found an excuse to visit the military tribunal and, while they were there, stole blank originals. Meanwhile, a friendly female guard, Schlitzer, gave Marcella a real release document, signed and stamped.

They filled in each blank form with the name of a prisoner and Marcella trained herself to copy the signature of the military attorney from the real document. She used a sheet of glass to magnify it, making sure that each copy was millimetre perfect.

They would also have to use authentic looking stamps. By chance, Marcella knew someone who worked in a business in Via Pié di Marmo, where they produced them. She asked her contact to make one for her that was identical to the tribunal stamp.

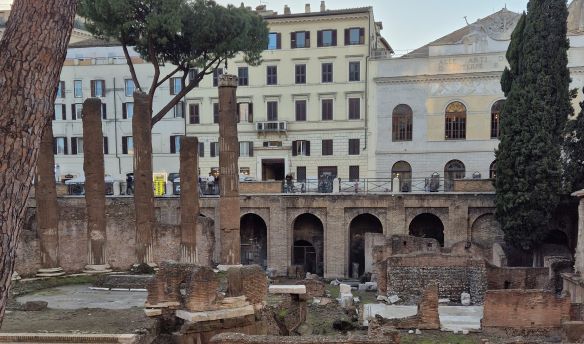

Via Pié di Marmo is about a forty-minute walk from Regina Coeli. In Shadow Song it is the location of Signor Ferraro’s art shop. Today, the street is home to many small shops, and the presence of a real art shop is entirely coincidental.

Almost time

The papers were ready.

Alfredo asked the friendly guard, Schlitzer, to tell Pertini (in Alfredo’s eyes the leader of the seven prisoners) to pretend to be taken ill overnight. That way, Alfredo could speak to him more easily. Pertini suffered “a sudden attack of appendicitis”, which enabled Alfredo to visit him and tell him about the plan to escape.

Meanwhile, Marcella tried to pave the way with the prison governor. Carretta’s lodgings were close to the Monacos’ apartment and Carretta was friendly with the family. Marcella mentioned that she had heard about a likely release of some Italian wing prisoners. Carretta seemed to take note, although he made no comment, and Marcella hoped that he would remember when he received seven release papers.

Meanwhile, Pertini kept sending messages from his sickbed. They were hidden in a flask and Marcella was terrified that they would be discovered but, to her relief, it was finally time to escape.

Alfredo visited Pertini, once more at night, and told him that the escape would happen the next day.

Schlitzer told Marcella that she would be on guard at the switchboard from one in the afternoon. She would take the papers to another sympathetic guard, Gala, who would also know that the papers were false. Gala would log them and send them immediately to Carretta.

Escape day

Just before one in the afternoon on 24 January, Marcella entered the main entrance of Regina Coeli. She was greeted by the corps of guards, a mixture of SS soldiers and Italian prison guards, who all knew her well. No-one was suspicious and they allowed her to pass. She made her way to the small office on the ground floor that housed the switchboard. Schlitzer was waiting and took the release documents from her. Marcella left to return to the apartment, and Schlitzer quickly took the papers to Gala.

When Gala gave Carretta the seven release documents, Carretta called Marcella on the internal telephone. He said that release papers had arrived for several prisoners, as she had predicted, but, he explained, the administrative command had recently issued a new order. He now had to send political prisoners to the police headquarters’ political office for authentication and subsequent release. There was only one way to avoid this: if police headquarters telephoned him, ordering him to let them out, he could do so. It was already four-thirty, Carretta reminded her, and the curfew would begin at five.

Marcella had known nothing about the new administrative procedure and realised that they would have to make a fake call. She was with a fellow group member, Lupis, and quickly explained the problem. Lupis offered to impersonate a police officer but they could not make the call from the Monaco apartment in case it was traced.

They ran to a public telephone and found that the prison line was busy. They kept trying, telephoning from one local business then another, but the line was still engaged. In desperation, they called the switchboard of the telephone company, who told them that it was almost certainly a fault on the prison line.

By now, the curfew had begun, and Marcella and Lupis were close to giving up. Then Marcella thought of her brother, Luciano: he was in Rome with the PAI (Polizia Afrika Italiana) and worked from a former carabinieri barracks. Months ago, Luciano had found a telephone there with two buttons. As he had told Marcella, one of those buttons accessed a direct line to Regina Coeli.

Marcella and Lupis quickly found Luciano, who led them to the telephone. Lupis, pretending to be an officer at police headquarters, called Carretta and told him to release the men, which Carretta agreed to do.

Marcella and Lupis raced back to Regina Coeli, hoping that the seven men would now be free to leave.

There was one further formality: the seven had to sign for their personal belongings. One man noticed that his cufflinks were missing from the bag he was given. He started to argue with the guard, unaware that this was not an official release. Pertini had to grab him and whisper in his ear that they were escaping. The man turned pale, stopped arguing and the seven men left.

Outside

They had to be careful because the curfew had begun. Five men vanished; one lived in Via San Francesco di Sales, next to the prison, and others may have gone with him. Marcella grabbed Pertini and Saragat, the two who remained. She walked with them a little, then they turned into a small alleyway, Vicolo del Buon Pastore, that runs past the rear of the prison. From there, they returned to Via della Lungara and entered Marcella and Alfredo’s apartment.

Via San Francesco di Sales.

The prison is on the right and borders the road.

Vicolo del Buon Pastore is further up the road on the right.

The aftermath

Pertini and Saragat remained hidden for two days in Marcella and Alfredo’s apartment before they finally left.

The next evening, Radio Londra (officially banned in Rome) announced the escape, although not how it had taken place. Within minutes, Marcella heard uproar in the prison but, to her relief, no-one guessed her involvement.

Kappler, the SS chief in Rome, demanded an explanation from Carretta, who responded calmly, saying that he had merely followed orders.

This story was first published in “Avanti”, and then in “Roma Sotto Il Terrore Nazista” by Armando Troisio shortly after Rome was liberated.

Marcella Monaco’s recollections were later recounted in “Roma Città Prigioniera” by Cesare de Simone.